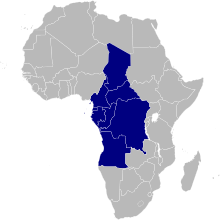

This sub-region which is often referred to as the “hot” zone of Africa, with regards to conflicts and civil wars, is still very diffident in political, economic and socio-cultural development.Youth policies, youth issues, youth budget and their participation is still very blurred in this sub-region. The sub-region is lagging in the 15 priority areas of the WPAY that is;

- Education

- Employment

- Hunger and Poverty

- Health

- Environment

- Drug abuse

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Leisure-time activities

- Girls and young women

- Full and effective participation of youth in the life of society and in decision-making

- Globalization

- Information and communications technology

- HIV/AIDS

- Armed conflict

- Intergenerational Issues

This write-up assesses the state of Youth Policies in this sub-region, as well as proposes the way forward for a better implementation of youth policies.

- THE STATE OF YOUTH POLICY (YP) WITH REGARDS TO THE 15 PRIORITY AREAS OF WPAY

We shall analyze the state of YP on a country to country basis, with regards to the 15 priority areas of WPAY:-

Angola:

The state of youth issues is better at the post-war, but yet the youth development index is very low 0.31. The national youth plan identifies several areas of action, including integrating youth in governmental institutions, promoting leisure and exchange, improving education and teaching, invest in citizenship education, improving health outcomes, the establishment of a youth/student discount card, promoting sports as well as youth entrepreneurship. Angola has a Ministry in charge of Youth Affairs, a National Youth Council and a National Youth Plan.

Cameroon

Young people in Cameroon face difficulties in accessing decent employment. Unemployment and underemployment levels are very high among young people. … Approximately 11% of youth aged 15 to 29 years are unemployed, particularly in urban areas. Underemployment affects approximately 94 % of young people aged 15 to 19 years and 84 % of those between 20 and 24 years.

The majority of job seekers abandon studies before completing the primary education (only 56% of the population that went to school also completed primary education). Since the advent of the economic crisis experienced by the country, the number of highly qualified young people without job prospects is of increasing concern.

In total 28.4% of adolescents [girls] aged 15 to 19 years had already had a child (22.7%) or were pregnant with their first child (5.7%). Over 40% of adolescents had already begun childbearing.

Young people are more affected than other age groups by HIV. The rate of HIV prevalence in the age group 25-29 years is 7.8% against 5.5% in the general population. 10.3% of young women and 5.1% among young men are affected.

The situation of young people concerning participation in social life and decision-making is characterized by a low level of involvement. This can partly be explained by a lack of organization and inadequate training of young people due to an inadequate legal framework and the lack of an advisory youth council, and also by the reluctance of adults to involve young people in the decision-making process. This reluctance is the consequence of generational conflict, lack of spaces for dialogue between adults and youth, and low representation of young people in decision bodies such as parliamentary assemblies, municipal bodies, and the community.

The national youth council of Cameroon (CNJC), which was created in 2009 as representative platform Cameroon’s youth, has been criticized for not effectively representing Cameroon’s youth. It is said to be too dependent on the government and its agenda.

Central African Republic:

This country has been recently plagued with political and religious turmoil and a greater proportion of youths are either direct protagonists in the coup d’état or are manipulated or are victims. Apart from the chaotic political landscape, youth policies and legislation is yet to be implemented. A National Policy for the Advancement of Central African Youth was drafted since 2009 and is not yet implemented. There is a Ministerial department in charge of youth issues. There exists a National Youth Council of the Central African Republic, which aims at promoting the growth and development of youth, the mobilizing and coordination of the actions of young people and to defend their interests at national and international level. It aims to promote a national youth policy, involve youth in decision-making, provide training on social values and culture of peace as well as promote participatory democracy.

Chad

Though Chad possesses a Youth Council and a Ministry in charge of youth matters, there is no clear indication of a total commitment to youth related issues. In 2012 a forum on the “Implication of Youth in Chad´s Development Policies and Programmes” was organized by the Coordination of Chad Youth Networks. The forum called for greater participation of youth in the country´s development framework, and for the formulation of a national youth policy. Despite the improvement in school enrollment rates, the country’s youth still suffers from low literacy rates -in 2009 only 46,3% of people aged 15 – 24 could read and write). According to Open Democracy, in 2012, only 9% of students successfully passed their high school leaving exams.

The article points to the fact that “80% of community-based schools and public schools are located in rural areas where they welcome 67% of the national student population. These schools remain seriously under-resourced in terms of both infrastructure and access”. In addition to demographic growth, which places pressure on Chad´s limited infrastructure, the country is host to refugees from Central African Republic (CAR) and West Darfur.

The Democratic Republic of Congo

This country, which has one of the largest surface areas, with a very rich subsoil have experienced conflicts for many decades now The war claimed an estimated three million lives, either as a direct result of fighting or because of disease and malnutrition. It has been called possibly the worst emergency in Africa in recent decades and a greater percentage of the victims are youths.

DR Congo has the lowest youth development index, 0.17 though with the existence of a national youth policy, a youth council and a ministry in charge of youth affairs. The state of youth participation is still very questionable. The population of the DRC is young and rejuvenating over 68 % of people aged less than 25 years, a majority of whom live in rural areas (over 60 %). The median age is 21 years passes in 1984 and 15,5 years in 2009. This situation reflects a high degree of dependence the persons responsible for creating the inability of workers to save. In addition, it causes a significant pressure on social and health infrastructure and the environment.

Republic of the Congo

Congo Brazzaville is another country from the Central African Sub-region, without a youth policy. Policies on youths are still in thoughts, they not yet documented, talk less of being enacted. A Code of Conduct for New Congolese Youth (NJECO) has been setup, but much still needs to be done. The Ministry of Youth and Civic education instituted the selection of the National Youth Council of Congo (CNJ-C) executive on 16 January 2014), the said youth council is yet to be implemented. Notwithstanding, the country has a ministry in charge of youth affairs, but the national budget on youth matters is very vague.

Equatorial Guinea

So far, there is no policy on youths, but so far The National Economic Development Plan: Horizon 2020 commits finances to social development priorities including education, gender equality, and community development as well as the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, which are priority areas that touch youths. There exists a ministry in charge of youths but According to the North-South Centre of the Council of Europe (2012), Equatorial Guinea is one of the “two countries in Central Africa that still lack national youth platforms.” Equatorial Guinea has signed the African Youth Charter, which according to Africa Youth “aims to strengthen, reinforce and consolidate efforts to empower young people through meaningful youth participation and equal partnership in driving Africa’s development agenda.” However, it has not been ratified. The National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES), which seeks to diversify the economy, envisages measures that indirectly help youth employment. The creation of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) should be boosted by an improvement in the overall business climate. Policies to enhance access to credit should be encouraged from 2012 to help the creation of SMEs and private initiatives. A new law requiring the administration to take on young people with qualifications and university diplomas was partially put into practice in 2011. The law lays down a maximum quota of foreign workers that a business can recruit (30% of the workforce in the oil industry and 10% in the non-oil sector).

Substantial progress has been made in secondary and higher education in recent years. Higher education is free and private education in the secondary sector is available and affordable. The basic secondary education program (ESBA), launched at the beginning of the 2000s, has been completed and the amount of technical training increased, especially in the private sector. The government plans to create technical and vocational training centers in the seven provincial capitals. Two centers are already in operation.

Gabon

In 2011, a youth forum was organized, which led to the creation of a youth policy, with the following outcomes:

- Sharing positive experiences for building an emerging Gabon;

- Youth self-awareness of their role;

- The adoption of the youth policy document by all actors;

- The reinvigoration of the National Youth Council of Gabon as a common platform and federation for youth organizations and movements;

- The creation of an observatory for the evaluation of the national youth policy;

- The assignment of a meeting center to the National Youth Council of Gabon;

- The launch of the President’s prize to celebrate the best youth entrepreneurs.

Though Gabon enjoys one of the highest GDP per capita in the continent, youth unemployment remains high. The government, with support from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the country’s civil society organizations, has developed the Country Programme for Decent Work (PPTD). The Employment Forum report (2010) highlights the heterogeneous nature of youth unemployment. The report places emphasis on encouraging entrepreneurial initiatives, through training youth experts, bridging the gap between education and the skills in demand in the labor market.

São Tomé and Príncipe

STP is one of the smallest economies in Africa with over 180,000 inhabitants and a per capita Gross National Income (GNI) of about US$2,080 (2011, PPP, current international $). Though STP has a ministry in charge of youth affairs; there is no national youth policy, no youth network or council, therefore, much still need to be done in order to revitalize youth inclusiveness. In 2009, the government set a minimum wage for youths below that for those with similar qualifications but greater experience. The initiative, which was intended to foster youth employment, was conceived in partnership with the private sector with the authorities paying half the youth’s salary. However, the scheme failed to have an impact due to the lack of a legal framework to sustain the arrangement. Youth integration into the labor market suffers from the absence of a youth employment policy and the lack of an information exchange mechanism between job seekers and employers. Underlining these challenges is the average post-graduation period of inactivity, which is five years.

- LAPSES

3.1 Conflicts and manipulation: What is very clear is that youths are always at the core of conflicts, they are often victims or protagonists. The central African sub-region has the highest number of conflicts in Africa. For instance, Angola gained independence from Portugal in 1975 after a 13 years guerilla war (1961-1974). However, after independence, Angola became involved in a civil war that lasted for almost four decades. The Democratic Republic of Congo formerly Zaire is a glaring example of a country bedeviled by the availability of natural resources. The DRC is potentially one of the richest countries in Africa endowed with a wide range of natural resources from oil, minerals, and timber. The fight for control of the enormous revenues flowing from the exploitation of these resources has been at the center of the violent conflicts in the DRC. The Congolese civil war has been described as one of the world’s deadliest war since the Second World War with an estimated 3.3 million deaths.

The Central African Republic (CAR) has for more than ten years been trapped in recurrent armed conflict with a civil war between October 2002 and March 2003. These years of armed conflict has led to a complete collapse of basic infrastructure, social services, and high insecurity. Of recent religious crisis have been aggravated with a majority of youths being victims, all is left at the mercy of MINUSCA.

The Congo-Brazzaville conflict began after the results of the first multiparty elections in 1993 that saw the defeat of Denis Sassou Nguesso who has been in power since 1979. Pascal Lissouba became President but his tenure was short-lived (1993-1997) as tensions heightened between his supporters and supporters of former President Denis Sassou-Nguesso ahead of the 1997 scheduled presidential elections which never took place as the country became immersed in a civil war that saw Denis Sassou-Nguesso come back to power.

Chad has been involved in a civil war (1979-1982) followed in 1989 with a short rebellion that led to the overthrow of President Hissen Habre. Chad’s first civil war had no direct linkage to the presence of natural resources because during this period until the start of oil exploitation in 2000, the country was considered one of the poorest countries in the world. Chad’s second civil war which began in 2005 could be described as having a direct link to the country’s emergence as a producer of oil.

In some instances, the civil war is described as a “spillover” from Darfur, Sudan and to an extent, these two wars are entangled. For several years, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea have been engulfed in a dispute over the sovereignty of the potentially oil-rich islands in Corisco Bay. The dispute over these islands has on several occasions brought these two countries at the brink of war. While Gabon has recognized Equatorial Guinean sovereignty over the inhabited islands, it has refused to do so over the three uninhabited islands of Mbanie, Coctotiers, and Congas probably because of the high chance of finding more oil in the islands. Cameroon has been described as an island for peace in a region marred by conflict. In 2009, Cameroon was considered by the Global Peace Index as the 95th safest country in the world from 92nd in 2008 and 76th in 2007. Notwithstanding, Cameroon experienced a coup d’etat in 1984, turmoil in 1992, during the institution of multipartyism and 2008 uprisings.

3.2 Very limited participation

Youth participation is the involving of youth in responsible, challenging action that meets genuine needs, with opportunities for planning and/or decision-making affecting others in an activity whose impact or consequence is extended to others— i.e., outside or beyond the youth participants themselves. Other desirable features of youth participation are provision for critical reflection on the participatory activity and the opportunity for group effort toward a common goal. Youth’s participation in decision making is an issue that this sub-region faces most as regards policy implementation. All the National youth policies, where they exist has a very limited online presence, youths are suppressed by Government institutions.

They are generally under the following tenets:

- Youth councils

- Participatory action research

- Youth-led media

- Youth-targeted political organizations

3.3 Under development

The HDI in the region is very low, apart from conflicts, most of the economies in central African

Sub-region are a plaque with poor governance, poverty, and very low infrastructural development.

Youth’s employment remains a very problematic domain; more than 70% of graduates remain either unemployed or underemployed

3.4 Insufficient political willingness

Countries from this sub-region, just like most countries from other regions of Africa are subjected to dictatorial regimes, characterized by extensive patronage systems, manipulations, and poor governance, making youths to be completely spurned from decision making. There is a total negligence.

- THE WAY FORWARD

4.1: National Youth Policies

In this sub-region, most countries like Equatorial Guinea, Chad, Central African Republic, Sao Tome and Principe and Congo Brazzaville, does not have national youth policies, meaning there is no legislation so far as youth policies are concerned…

The way forward is an urgent adoption and legislation of youth policies.

On the other hand, other countries like Angola, Cameroon, DRC and Gabon have National Youth Policy since 2006, but till date the texts do not match with the realities, most of these policies are only on paper.

The way forward is full implementation of these policies, its inclusion in national policies and a full independence and participation of youth networks

A national youth policy needs to be representative and for this to be eminent, a national youth council needs to be created, one that is independent, inclusive, apolitical, create outreach programs and constitute a steadfast network.

4.2 Youth Budget

Because of poor governance and the lack of political willingness, there are no clear data as regards the budget that is allocated to youth related activities. In all the countries of the sub-region, there exist ministries in charge of youth affairs, but a greater proportion of their budget is for office supplies, outstation allowances, and other non-youth-related activities.

The way forward is the legislation of youth budget, by allocated specific and well-defined amount of money to youth councils and other youth movements. The budget allocated to youth councils and youth empowerment activities should be detached from other priority areas, all the governments needs to do is to institute control mechanisms, not to control the budget.

4.3 Participation

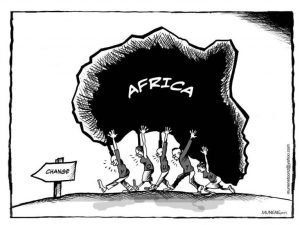

As regards participation, a majority of youths from the Central African Sub-region only participate in conflicts and coup d’états, rather than in national development.

They are shunned in all the arms of power, be it legislative, judiciary or executive. All decisions are taken by aged government bodies and political leaders, pushing the youths to a yes-yes machine.

The way forward is an inclusive mechanism, one that will put the youths in the limelight; we have for instance improving access to information in order to enable young people to make better use of their opportunities to participate in decision-making.

Online presence; youth councils and youth bodies should have functional websites for greater visibility and participation, only the youth councils of Gabon and Angola has functional websites, the rest are either in existent or non-functional. Youths should also network on social media.

Opened dialogue mechanism; Bottlenecks should be disrupted, the gap between government bodies (especially ministries in charge of youth) should be bridged. Forums on youth policies should be created for dialogue, thus developing and/or strengthening opportunities for young people to learn their rights and responsibilities

Participatory monitoring: this means making sure that young people themselves are assisting in assessing how their country’s policies and programmes are affecting them, and to what extent meeting their needs this will help to Measure progress, Identify strengths and weaknesses, Assess effectiveness, determine the costs & benefits, and Collect information, Share experiences, Improve effectiveness, Allow for better planning and be accountable to stakeholders. Encouraging and promoting youth associations through financial, educational and technical support and promotion of their activities.The presidents of youth councils or their entire bureau should participate in decision-making instances like law making, voting of the budget, political appointments, and the judiciary, thus taking into account the contributions of youth in designing, implementing and evaluating national policies and plans affecting their concerns.

4.4: Networking

A sub-regional network of youth ministries, as well as a cross-sectorial approach in their intervention, youth-led INGOs, youth councils, youth legislators and youth policy practitioners, should be instituted in the Central African sub-region. This will create an enabling environment on best practices as regards youth policies. This network of youth policy practitioners can be affiliated to the two regional economic blocks, CEMAC and ECCAS and later on link up with other sub-regional networks, the AU and most importantly youthpolicy.org.

4.5 Setting up a guiding mechanism to monitor Youth Policies, for instance

1: National youth mechanisms

■ Does a youth policy exist in your country? Is it cross-sectoral? Does it have specific, time-bound objectives? What about evaluation mechanisms?

■ What type of youth department or youth ministry exists in your country? How does it coordinate with other ministries? Is it cross-sectoral?

■ Does the youth department/ministry conduct research and data collection on youth-related issues? How are these findings disseminated?

■ What types of national coordinating mechanisms exist? How are youth policies integrated with youth programs?

■ What is the involvement and participation of youth and youth organizations in the existing institutions and mechanisms?

■ What have been the successes and constraints?

2: Highlighting a youth organization

■ What makes this particular organization worthwhile?

■ Does this organization fully represent all youth? Is it gender balanced?

■ How does this organization work with the government and NGOs?

■ What types of programs does this organization implement?

■ What have been the successes and constraints?

3: Highlighting a youth project

■ What makes this particular project worthwhile?

■ Does this project take into consideration gender concerns?

■ How do youth participate in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the project?

■ How does this project fit into the overall government or NGO program?

■ What have been the successes and constraints?

4.6: setting up Indicators to Monitor and Evaluate Youth Policies in the Central African

Subregion, using the EU model, proposed Tanya BASARAB, Youth Work Development

Project Manager, European Youth Forum

INDICATOR 1: Non-formal education.

While it is important to pay attention to the conditions for young people in the formal school system and at the universities through policies of formal education, the cornerstone of a ‘youth policy’ is its focus on how young people can become active citizens and positive contributors to society. This implies a much wider perspective, and an emphasis on non-formal education – education outside the formal school system. How can government policy encourage and promote an active learning process of young people outside the formal school system? Youth initiatives, youth clubs and non-governmental youth organizations, which are actively involving young people at all levels, and where young people themselves decide upon activities, play a central role in developing young people as active citizens in society. Governments should see it as an important task to promote the development of active and strong non-governmental youth sector, composed of democratic, open and inclusive youth associations that involve young people.

INDICATOR 2: Youth training policy.

The government should promote the development of good trainers in the youth sector so that these trainers again can act as multipliers in raising awareness on diverse issues. These trainers can also better facilitate the development of the non-governmental structures in the youth field. A training policy is a prerequisite for better structuring the non-governmental sector.

INDICATOR 3: Youth legislation.

There needs to be a youth legislation that corresponds to the other dimensions of a proactive youth policy. Such legislation should acknowledge the involvement of young people and youth NGOs in policy decision-making, and make the legislative framework for an efficient government administration to work with youth issues.

INDICATOR 4: Youth budget.

In line with the strong recognition for associative life and non-governmental youth organizations outlined in INDICATOR 1, there needs to be a budget for promoting the development of youth initiatives and youth organizations. In order to promote the development of a sustainable youth NGO sector, the government should allocate administrative grants to youth organisations that enable them to run a secretariat and otherwise carry out tasks that are not specifically project related (statutory meetings, communication with members, etc). There also needs to be a state budget allocated for the realization of activities to be carried out by the youth NGO sector, meaning that the government should allocate project grants for youth activities.

INDICATOR 5: Youth information policy.

A youth information strategy should ensure transparency of government policy towards young people. Such a strategy should also inform young people about different opportunities that exist for them. Different initiatives that can be elements of a youth information strategy can be the publishing of a youth magazine and other information material and ensure open communication channels with networks of all major stakeholders for youth policy.

INDICATOR 6: Multi-level policy.

A national youth policy should outline steps to be taken and policies to be implemented not only at the national level but at all levels of government administration. A national youth policy can not become a reality without focusing on what needs to be done at the local level, and with the active involvement of local government authorities.

INDICATOR 7: Youth research.

A youth policy should be based on research about young people. A policy should not be based on assumptions and speculations, but rather on facts and research on young people. This should help to determine what should be the focus of government policy. Youth research should address issues relating to the well-being and the situation for young people. However, youth research should also focus on which policy measures that work and which that doesn’t, measure how youth NGOs can play a role in promoting youth participation etc.

INDICATOR 8: Participation.

The cornerstone of a youth policy should be the active involvement and participation of young people in society. A youth policy must address how young people can be included in decision-making processes. How will government officials involve young people when making decisions that affect young people? Furthermore, how can a youth policy facilitate a process where young people participate and contribute actively to society? There is a long tradition in Europe for involving non-governmental youth organizations and youth councils (“umbrella-organisations” of non-governmental youth organizations) in government decision-making. Youth organizations have for more than 30 years had a strong influence on programs and activities in the youth sector in the Council of Europe, through the principle of “co-management”. Youth organizations at all levels took an active part in the consultation process which preceded the White Paper on Youth Policy which has been adopted by the European Union. Active involvement of non-governmental youth organizations on issues concerning young people is practiced in most European countries. Youth organizations also play an important role in involving young people, making them active citizens in their own society. Encouraging and facilitating the active participation of young people in non-governmental youth organizations should be a central element of a youth policy.

INDICATOR 9: Inter-ministerial co-operation. Inter-ministerial co-operation.

A dynamic and comprehensive youth policy need to address the diverse needs of young people in all sectors of society. A cross-sectoral approach is needed in youth policy development, meaning that it should be the joint responsibility and depend on the joint cooperation between a range of ministries with different portfolios such as youth, sport, education, culture, defense, health, transport, labor, agriculture etc. etc. One possible way of assuring cross-ministerial cooperation is to establish an inter-governmental committee to work on the development, implementation and monitoring of a youth policy.

INDICATOR 10: Innovation.

A youth policy should promote innovation, by thinking creatively how to solve challenges, and to stimulate young people to be creative and innovative.

INDICATOR 11: Youth advising bodies.

In order to assure the consultation and partnership between the government on one side and young people and youth organizations on the other, a structure should be established (such as a consultative committee) which is consulted and given the mandate to influence government on issues regarding young people. Not only should such a structure exist at the national level, it should also be developed at all different levels of government administration.

CONCLUSION:

Youths should no longer be seen as “the future of tomorrow, but rather today’s upholders”, it all commence with good policies, legislations, and political willingness. Their energy, vitality, creativity and innovation is imperative in any development agenda. Youths from the central African Sub-region are shunned, generally, because they are regarded as part of the problem and not the solution. Most of the countries do not have a national youth policy, nor a youth council, others have neither signed nor ratified the African Youth Charter, which is a problem. There is an urgent need for these countries to comply with the WPAY.

Ref

www.youthpolicy.org

http://www.cjdhr.org/2009-06/Durrel-Halleson.pdf

Tanya BASARAB, Youth Work Development Project Manager, European Youth Forum

youthforum@youthforum.org

By Mbuih Zukane

Senior Youth Worker,

MA International Cooperation Humanitarian Action and Sustainable development,

Community Manager, SIC, University of Dschang, Cameroon,

Director of Finance and Audits AfriNYPE.

mbuih.zukane@afrinype.dedicatedlinks.xyz

Edited by Seleman Yusuph Kitenge

Youth Development Expert,

PGD – Management of Foreign Relations, BA in Sociology (Hons),

Director of Media & Communication, AfriNYPE.

seleman.kitenge@afrinype.dedicatedlinks.xyz